Growing Up Different: Personal Roots and the Work of Growth

A reflection on childhood experiences, family legacy, and the ongoing journey of self-awareness

The Discomfort of Being Different

When I was a kid, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was a day off from school that sometimes made me uncomfortable. As a family, I can recall us remarking that while we attended an incredible private Catholic school, we were one of few families of color. I was fortunate to have more than a handful of classmates in my grade of close to forty students who came with diverse understandings of what family looks like here in America. But this experience of being different—and a knowing of the fight for equality—existed not only at our elementary school, but even in our neighborhood in Columbia, MD.

Growing up on Red Apple Lane in the eighties, I felt at home, and it was a painful day for our family when we moved away from this known community of friends and support. We had neighbors ready to help when our dad was away and snakes were in the garage. When a kid was being called, you might not have heard the name clearly, but we knew whose parent’s voice was summoning one of us home.

I now recognize that much of my experience at school wasn’t shared by those who I might have thought had it easier. My knowledge of my childhood neighborhood has also evolved as I’ve learned stories from those who experienced a more complex and mixed understanding of belonging.

At the same time, I uniquely remember traveling up the street often on MLK Day to visit our fellow military family’s home—who were, among more than dozens of homes, one of a handful owned by a family of color. It was an occasion marked with celebration and pride, as well as many laughs, but also an acute awareness that we felt differently about the day than the houses we traveled past. Even though these neighbors never showed hatred or lack of support for our being a testament to Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision, the reverence of this day still holds a connection to personal stories and family history of the tragedy in his death and the fight he had to fight.

Stories That Shape Us

I’ve grown up listening to stories about America’s past. To this day, my great-aunt and great-uncle can recount stories of their great-grandfather, who had lash marks down his back from his life in servitude. My mother’s family grew up in Washington, D.C., and as a kid, before the rise of the internet, I conjured images of trash cans and buildings on fire as I listened to my elders discuss the city ablaze when MLK was assassinated. Though the raging fires died, the embers that fueled the outbreak never fully dissipated, and we’re still left with much of a country living in a tinderbox.

On one side of my family, my father has traced our ancestry to my great-grandfather’s grandfather, who was enslaved and baptized by the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. On the other, my great-grandmother was one of 11 children born to William J. and Carrie T. Chisley, mentioned in a Washington Post piece from 1990. Papa, as my grandmother and her siblings referred to him, worked in the legacy of Frederick Douglass as a caretaker of his estate during the early twentieth century in Southeast Washington, D.C., when it was owned by his late wife Helen Pitts Douglass.

The stories my great-aunt and great-uncle share echo those captured by Mary Agnes Beatrice Chisley Price, one of my great-grandmother’s sisters. She describes herself in the article as “Bea Price… the price is right.” She shares how her grandfather William Henry Gaunt “kept… [them] spellbound, telling… slave and ghost stories.” Thanks to my master’s work for Goucher’s Master of Arts in Cultural Sustainability (M.A.C.S.), I have a recording of my great-uncle sharing one of his favorite scary tales from his great-grandfather Gaunt that he recalls listening to as a kid. I sat listening as he did, amazed and in awe.

I was raised in Columbia, MD, a city envisioned by a real estate developer’s mind that spoke to the turmoil of the late sixties and a belief that the spaces where we live and work together shape much of what we feel and believe about ourselves and our sense of belonging in community. I cannot say I always felt like I belonged in Columbia in the eighties, but I also cannot say that I was made to feel like I didn’t by the families I grew up with on Red Apple Lane and surrounding cul-de-sacs.

Learning From My Grandmother’s Pain

When my immediate family moved outside the confines of this unique social experiment to Ellicott City, I came to better understand the stories I heard from my grandmother, Shirley Mae Greene, who grew up in Ellicott City, MD just off Main Street on Old Columbia Pike. As a little girl, I grew up listening to my grandmother recount pain and hardship from growing up segregated in Howard County. Friends who would play with her one day would ignore her and make her feel invisible the next, depending on surrounding company.

I must admit, as I strolled through a grocery store the other day, I turned my head in fear of recognition and against my instincts for connection. I’ve been disappointed by this individual before, and I’m still learning how to let go of very real disconnects about who has value in our society—who we see as worthy of conversation and who goes unseen. I truly feel sorry for any human I made feel small through my ignorance and hurt from my own past hurts and insecurities. The echoes of my grandmother’s experience still reverberate today in many social circles in Howard County, MD.

I know we aren’t all going to get along. I fully accept that I am not everyone’s cup of tea and appreciate that there are groups of people I too would rather not share space with for whatever reason—whether they see me with distaste or they feel comfortable sharing their distaste for others. Usually, if you believe in hierarchies of worth and value, we will most likely find ourselves in uncomfortable moments of disconnect.

Triggers and Growth

Words are as sharp as knives, and no matter who wants to tell me to let them roll off my back, my back like my ancestors’ is riddled with scars from my journey. My faith is in the forever gift of progress—becoming a better version of myself every day. I want to open myself up to the table of accountability—I am human. I can get hurt, and it’s often when an old wound gets hit that I still find myself navigating my emotions as a human living with others and hurting out of blind, tired, or knee-jerk reactions in my weakness as a human.

I don’t want anyone to feel uncomfortable around me or like they need to be “on,” and yet I do believe in and am grateful for my family and community who allow space for being both “on” and “off” with intention and purpose—grace without excuse, but understanding and acceptance with a foundation in mutual respect and accountability. I hear myself saying this and it all sounds idealistic and elusive. I too know there are many who will roll their eyes and turn the page or spread hate: “Who does she think she is?”

I’ve carried a hurt around that, as I watch my young son discover his identity, I feel compelled to share. This is often triggering, so I offer warning that I’ll share my painful truth about race. It’s not rare or unique, but it’s where I still find I need to give myself grace and make space for others who don’t realize, can’t understand, or are only starting to understand race and the responsibility that so many carry with having it labeled upon us.

I was told around 10 or 11 years old that my first crush could not date me because he had to date someone who was “blonde and blue-eyed.” I know for many still today, this is completely reasonable, and for me to think otherwise justifies why I’m a person to be ignored and kept away. If I’m honest, my grandmother, who experienced years of segregation and racism in her youth, would most likely be disappointed by the lack of rich color in her continued offspring—our family has gotten lighter, not darker, over the generations.

This said, as we speak, institutions like the Smithsonian—a huge partner in elevating the broader narrative of our American history and reconciling with truths of much of our early legacy—might be seen by some as a proponent for retribution due to this reconciling. To me, this feels like an assault. As I said, I grew up visiting D.C., visiting family, visiting the museums, our nation’s monuments, the history of our country and the legacy of democracy that so many who came before me fought to protect—all people’s right to have a voice despite difference and a belief we are stronger together than against each other.

We’re living in a time where many want to see the trauma of my family as a benefit, where my shame as a kid and the discomfort of my experience is deemed okay. It’s okay for me to have experienced it, but not okay for today’s kids who don’t have to heed warnings from their family about the true history that for years was denied—the right to have their story shared fully in the light. Some want that history put back into the dark because of the discomfort it causes.

I won’t let my ancestors’ story be hidden away because of the discomfort and responsibility that people do not want to feel. While I understand this feeling, I know those walks up the street on Martin Luther King Jr.’s Day gave me a pride that today can’t shake my fear of pressing publish on this piece. My family’s story matters. This work—the small, the daily, the everyday reckoning—matters.

As a little girl, I learned that no matter how far my life had come in the eyes of my great-grandmother as she watched her granddaughter raise a family in a blended community, I still understood that I was never going to be seen as equal. I grew up knowing that no matter my life choices, my grades, how well I spoke, or how presentable I appeared, I would always be unworthy to some of love and respect, of understanding and value—knowledge that brings pain to kids barely knowing what it means to be human and have a voice.

In my preteens and into my early twenties, I struggled with my value, my talents, my gifts and went down several destructive paths. Looking at myself for eight hours a day doing studio time studying theater really made me look honestly at myself. I saw with more clarity where we can get lost and lose our way in our narratives. I lost myself in the narrative of who I had to be as a successful daughter, student, sister, friend. I felt like I was losing myself having to choose: Am I an actor? An actor of color? A girl from the suburbs? Or a girl who knows the history from where she came?

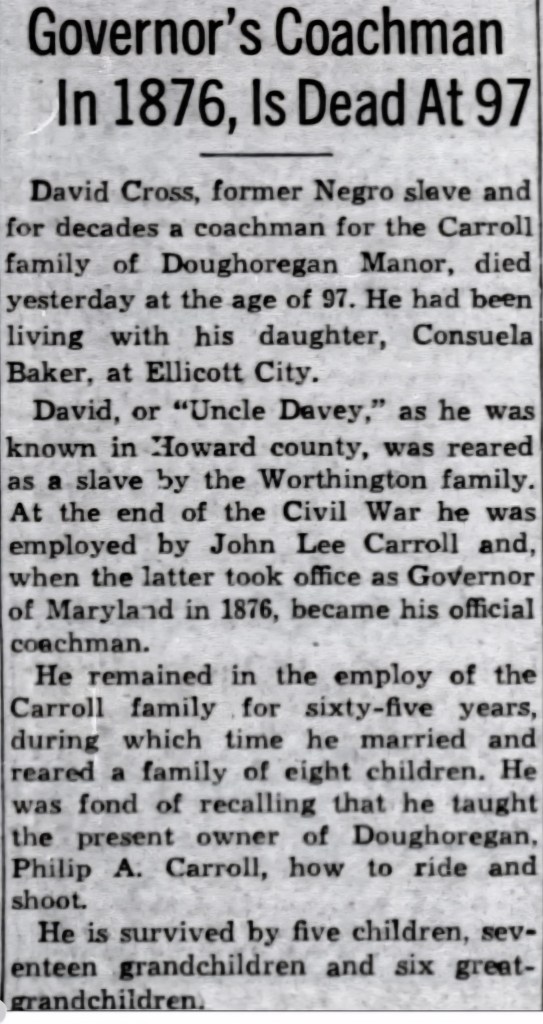

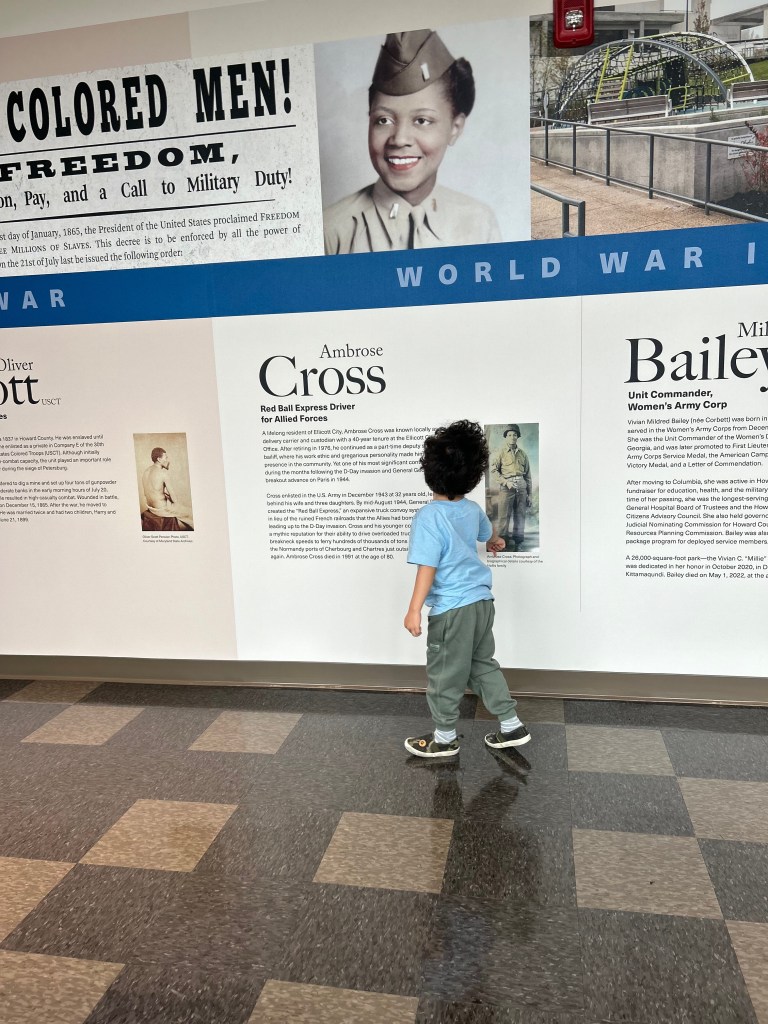

At the time, I had no idea that during those early morning drives to high school, driving past the old manor, feeling eerie sensations like I was not alone, I was traveling the same paths as my ancestor David Cross—whose life I can barely begin to fathom. Thanks to my father’s meticulous genealogical research, we’ve learned that his nickname of “Davey” came years before the legend of Davy Crockett was ever born. History known can rewrite the tales we tell.

What a difference this knowing would have made as I continued to face racism while attending a private school in Western Howard County. While the school itself celebrated diverse voices and cultures—many who live with legacy at the time did not believe my DNA should mix with theirs, let alone belong in Western Howard County. It’s a reality that to this day, as a human on this earth, is easy to separate as a rational understanding and desire. It’s the way many looked at our family, as we again encountered being one of few to the neighborhood. This time however, I began to understand that people saw the ethos of Columbia spreading to Ellicott City—keeping separate was only getting harder, and the desire to protect this “unique knowing” became stronger.

It’s not a sign of being racist—it’s a sign of… I’m not sure. I just know I’ve lived it and it hurts, but I also get it. It’s not intentional. It’s the culture so many just want to protect. No one wants to feel bad for protecting what feels so precious and precarious and special and unique. I don’t want anyone to feel bad, and yet here I sit in this murky understanding of being human and living as the person a family needs to protect from.

I fear my son will reject me in his choice of partner. Though, that would make me determine that there is a part of him he can choose as he walks in this world knowing that his DNA is not one or the other, but both mother and father. Whoever he chooses, if he chooses at all, I only hope has character and a heart that will support the beautiful human we’re doing our darndest to raise. That is all I can hope and dream for him. However that looks is up to the Good Lord above. I trust and believe in my family no one feels betrayed. As I said, we’re a beautiful kaleidescope of color and culture, love and commitment, patience and faith.

It’s easy to give space for all who simply love who they love, not as a choice, just as an attraction and discovery and eventually a choice that is what it is. I also want to give space to those who make the choice to love who they love to not “mess up their family’s lineage”—who don’t want to be part of changing the course of their family’s legacy. This choice is common—global, even. However, if we look at the globe, where in this choice do we develop the need to bring out the weapons and choose violence and terror? What’s the test limit? How can we make the world less riddled with fear—fear that causes people to amp up anger in the name of protection, but creates fuel for the fire? The tinderbox will never be put out this way.

Now, to all those families and individuals who navigate the space in between race and identity, life and society, culture and faith. I sit with you. Over the past decade, I’ve often thought how much easier it might have been if in my family we had “shared understandings”. Though even in the house I grew up in, “shared understandings” are mixed and often more complex than this simple framework would recognize.

I will live my life fully and always with the knowledge that who I am and how I show up is a responsibility I carry—not to assimilate or fit in, but for the integrity and respect that I walk confidently in, expecting treatment that my ancestors might not have received. I accept myself wholly for the beautiful complexity that exists within my DNA, my lived life, and personal story.

The Space for Contradiction

In my experience, when we interrogate hate and its roots, there is rarely a person who is not coming from a place of fear or hurt, and in some ways, there is an innocence here that is honest and authentic based on cultural understandings. I know, if I believe in this work, it is here that I wrestle and ask you to get in the mud of it and wrestle with yourself in this struggle. I’m not excusing bad behavior and real harms that people feel comfortable inflicting. But I also believe we must find space for the conflict that all of us hold inherently based on our personal designs and cultural understandings.

There should be a broader understanding of ideals, but I know this is a threat to whole cultures, ethnicities, and nationalities, so my American viewpoint, baked deeply in Columbia, MD, must leave space for the discomfort of the ideals that as a kid caused me harm. I must also find space for the conflict it holds with my human design and cultural understandings.

Our Collective Work

Life in its beautiful complexity has given me strong, beautiful, courageous, and vulnerable humans who have guided me. One in particular would sing my name in a way that made me feel valued and seen—and their eyes were blue and their hair was always blonde, even if by a bottle.

As I’ve said before, I do not claim to have answers. I offer my honest truths in an attempt to open up deeper conversation and to ensure that the history and legacy of those who helped me find the freedom to be on this journey of discovery get their light and glory. Together, we can ensure that the stories that matter are documented for future generations—to help provide guideposts, as my ancestors have for me, for the depth that lies in our future possibilities when we reconcile with the past honestly. Past, present, and future are all entwined.

The Beautiful Mess of Being Human

We’re all working in our own way with our angels, demons, strengths, weaknesses—however you call them. Few people are always perfectly happy within their human design, let alone life. These two things are separate, and we need to give more space for all people to live more comfortably, so we need to get comfortable being uncomfortable. I know this sounds counterintuitive, but we’re humans, so it most likely is. We’re weird, but beautiful. Let’s embrace our complexities and get more comfortable with ourselves as walking contradictions.

Maybe, if we can give space for ourselves to be this way, we can finally put out the embers and begin to heal from the ashes. Over and out from the murky middle…

P.S. In my family, mental health is a part of our everyday wellness. If you struggle or find yourself struggling, being human is complex and we can all use a team of support. Here are resources for immediate crisis needs in the U.S. and an invitation to all to take care of your whole beautiful self—mind, body, and spirit. If there’s anything I am here for, it’s the acknowledgment that it’s not easy and no one should feel alone or ashamed for wherever they are in the journey of life and being human. And to the first love of my life—forever like a firefly in the night, you live as one of the greatest gifts of this life. May your light live on in all who felt the spark of your brilliance, compassion, humility, kindness, and strength.

• National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

• National Alliance on Mental Illness: 1-800-950-NAMI (6264)

• SAMHSA National Helpline: 1-800-662-4357

This reflection is part of an ongoing conversation about how personal history shapes our present interactions and the work we must do—individually and collectively—to create more space for each other’s full humanity. Join the broader conversation at frankandethels.com/always-welcome by adding a comment and sharing your own reflections.

Leave a comment